Changes in Art From Neolithic Period to Ancient Near East

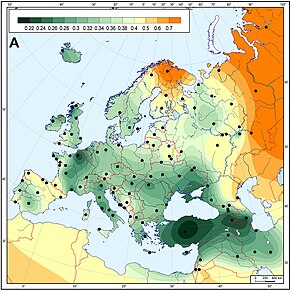

Chronology of arrival times of the Neolithic transition in Europe from 9,000 to iii,500 before present

Neolithic Europe is the menses when Neolithic technology was present in Europe, roughly betwixt 7000 BCE (the approximate fourth dimension of the outset farming societies in Greece) and c. 1700 BCE (the first of the Statuary Age in Scandinavia). The Neolithic overlaps the Mesolithic and Bronze Age periods in Europe as cultural changes moved from the southeast to northwest at virtually 1 km/year – this is chosen the Neolithic Expansion.[ane]

The duration of the Neolithic varies from identify to place, its end marked past the introduction of statuary implements: in southeast Europe information technology is approximately 4,000 years (i.east. 7000 BCE–3000 BCE) while in parts of Northwest Europe it is only nether three,000 years (c. 4500 BCE–1700 BCE).

The spread of the Neolithic from the Nearly East Neolithic to Europe was first studied quantitatively in the 1970s, when a sufficient number of xivC historic period determinations for early Neolithic sites had become available.[2] Ammerman and Cavalli-Sforza discovered a linear relationship between the age of an Early on Neolithic site and its altitude from the conventional source in the Nigh East (Jericho), thus demonstrating that the Neolithic spread at an boilerplate speed of virtually one km/yr.[2] More recent studies confirm these results and yield the speed of 0.6–1.3 km/yr at 95% confidence level.[2]

Basic cultural characteristics [edit]

An assortment of Neolithic artifacts, including bracelets, axe heads, chisels, and polishing tools.

Regardless of specific chronology, many European Neolithic groups share basic characteristics, such as living in small-scale-scale, family-based communities, subsisting on domesticated plants and animals supplemented with the collection of wild plant foods and with hunting, and producing hand-made pottery, that is, pottery made without the potter's bike. Polished stone axes lie at the centre of the neolithic (new stone) civilisation, enabling woods clearance for agronomics and production of wood for dwellings, likewise as fuel.[ citation needed ]

In that location are also many differences, with some Neolithic communities in southeastern Europe living in heavily fortified settlements of three,000–4,000 people (e.g., Sesklo in Hellenic republic) whereas Neolithic groups in Britain were small (mayhap l–100 people) and highly mobile cattle-herders.[ original enquiry? ]

The details of the origin, chronology, social organisation, subsistence practices and credo of the peoples of Neolithic Europe are obtained from archaeology, and not historical records, since these people left none. Since the 1970s, population genetics has provided contained data on the population history of Neolithic Europe, including migration events and genetic relationships with peoples in South Asia.[ original research? ]

A further independent tool, linguistics, has contributed hypothetical reconstructions of early European languages and family unit copse with estimates of dating of splits, in particular theories on the relationship between speakers of Indo-European languages and Neolithic peoples. Some archaeologists believe that the expansion of Neolithic peoples from western asia into Europe, marking the eclipse of Mesolithic culture, coincided with the introduction of Indo-European speakers,[iii] [ page needed ] [4] [ page needed ] whereas other archaeologists and many linguists believe the Indo-European languages were introduced from the Pontic-Caspian steppe during the succeeding Bronze Historic period.[v] [ page needed ]

Archæology [edit]

A rock used in Neolithic rituals, in Detmerode, Wolfsburg, Deutschland.

Archeologists trace the emergence of food-producing societies in the Levantine region of western asia to the close of the last glacial period around 12,000 BCE, and these developed into a number of regionally distinctive cultures past the eighth millennium BCE. Remains of food-producing societies in the Aegean have been carbon-dated to effectually 6500 BCE at Knossos, Franchthi Cave, and a number of mainland sites in Thessaly. Neolithic groups appear soon subsequently in the Balkans and south-central Europe. The Neolithic cultures of southeastern Europe (the Balkans and the Aegean) show some continuity with groups in southwest Asia and Anatolia (e.grand., Çatalhöyük).

In 2018, an viii,000-year-former ceramic figurine portraying the head of the "Mother Goddess", was found near Uzunovo, Vidin Province in Bulgaria, which pushes dorsum the Neolithic revolution to 7th millennium BCE.[half-dozen]

Current evidence suggests that Neolithic fabric culture was introduced to Europe via western Anatolia, and that similarities in cultures of N Africa and the Pontic steppes are due to diffusion out of Europe. All Neolithic sites in Europe contain ceramics,[ original inquiry? ] and contain the plants and animals domesticated in Southwest Asia: einkorn, emmer, barley, lentils, pigs, goats, sheep, and cattle. Genetic data propose that no independent domestication of animals took identify in Neolithic Europe, and that all domesticated animals were originally domesticated in Southwest asia.[vii] The only domesticate not from Western asia was broomcorn millet, domesticated in East asia.[8] [ citation needed ] The earliest evidence of cheese-making dates to 5500 BCE in Kuyavia, Poland.[9]

Archaeologists agreed for some fourth dimension that the culture of the early Neolithic is relatively homogeneous, compared to the late Mesolithic. DNA studies tend to confirm this, indicating that agriculture was brought to Western Europe by the Aegean populations, that are known as 'the Aegean Neolithic farmers'. When these farmers arrived in Uk, DNA studies prove that they did not seem to mix much with the before population of the Western Hunter-Gatherers. Instead, there was a substantial population replacement.[x] [11]

The diffusion of these farmers across Europe, from the Aegean to Britain, took almost 2,500 years (6500–4000 BCE). The Baltic region was penetrated a bit after, around 3500 BCE, and in that location was too a filibuster in settling the Pannonian apparently. In full general, colonization shows a "saltatory" blueprint, as the Neolithic advanced from 1 patch of fertile alluvial soil to another, bypassing mountainous areas. Analysis of radiocarbon dates show conspicuously that Mesolithic and Neolithic populations lived side past side for equally much every bit a millennium in many parts of Europe, specially in the Iberian peninsula and along the Atlantic coast.[12]

Investigation of the Neolithic skeletons found in the Talheim Decease Pit suggests that prehistoric men from neighboring tribes were prepared to fight and kill each other in order to capture and secure women.[thirteen] The mass grave at Talheim in southern Germany is one of the earliest known sites in the archaeological record that shows evidence of organised violence in Early Neolithic Europe, among various Linear Pottery civilization tribes.[fourteen]

Stop of the Neolithic [edit]

With some exceptions, population levels rose quickly at the showtime of the Neolithic until they reached the carrying chapters.[15] This was followed past a population crash of "enormous magnitude" after 5000 BCE, with levels remaining low during the next 1,500 years.[15]

Transition to the Copper age [edit]

Populations began to rise after 3500 BCE, with further dips and rises occurring between 3000 and 2500 BCE but varying in date between regions.[15] Around this fourth dimension is the Neolithic decline, when populations collapsed across nigh of Europe, maybe caused by climatic conditions, plague, or mass migration. A study of twelve European regions found about experienced nail and bust patterns and suggested an "endogenous, non climatic cause".[16] Recent archaeological evidence suggests the possibility of plague causing this population collapse, every bit mass graves dating from effectually 2900 BCE were discovered containing fragments of Yersinia pestis genetic material consistent with pneumonic plague.[17]

The Chalcolithic Historic period in Europe started from about 3500 BC, followed presently after by the European Bronze Age. This too became a flow of increased megalithic construction. From 3500 BCE, copper was being used in the Balkans and eastern and central Europe. Also, the domestication of the horse took identify during that time, resulting in the increased mobility of cultures.

Nearing the close of the Neolithic, effectually 2500 BCE, large numbers of Eurasian steppe peoples migrated in Central and Eastern Europe.[eighteen]

Gallery [edit]

-

Ancient Neolithic Greece stone grinder.

-

Neolithic site of Nea Nikomedeia, Northern Greece

Genetics [edit]

Ancient European Neolithic farmers were genetically closest to mod Anatolian and Aegean populations: genetic matrilineal distances between European Neolithic Linear Pottery Culture populations (5,500–iv,900 calibrated BC) and modern Western Eurasian populations.[19]

Genetic studies since the 2010s have identified the genetic contribution of Neolithic farmers to mod European populations, providing quantitative results relevant to the long-standing "replacement model" vs. "demic diffusion" dispute in archaeology.

The earlier population of Europe were the Mesolithic hunter-gatherers, called the "Western Hunter-Gatherers" (WHG). Later, the Neolithic farmers expanded from the Aegean and Almost East; in diverse studies, they are described every bit the Early European Farmers (EEF); Aegean Neolithic Farmers (ANF),[11] Start European Farmers (FEF), or as well as the Early on Neolithic Farmers (ENF).

A seminal 2014 study first identified the contribution of 3 main components to modern European lineages (the third being "Ancient North Eurasians", associated with the later Indo-European expansion). The EEF component was identified based on the genome of a woman buried c. 7,000 years ago in a Linear Pottery culture grave in Stuttgart, Frg.[20]

This 2014 study found evidence for genetic mixing betwixt WHG and EEF throughout Europe, with the largest contribution of EEF in Mediterranean Europe (especially in Sardinia, Sicily, Malta and among Ashkenazi Jews), and the largest contribution of WHG in Northern Europe and among Basque people.[21]

However, when the Neolithic farmers arrived in U.k., DNA studies bear witness that these two groups did not seem to mix much. Instead, at that place was a substantial population replacement.[10] [11]

Since 2014, farther studies have refined the picture of interbreeding between EEF and WHG. In a 2017 analysis of 180 ancient Dna datasets of the Chalcolithic and Neolithic periods from Republic of hungary, Germany and Spain, evidence was institute of a prolonged period of interbreeding. Admixture took place regionally, from local hunter-gatherer populations, so that populations from the three regions (Germany, Iberia and Hungary) were genetically distinguishable at all stages of the Neolithic period, with a gradually increasing ratio of WHG ancestry of farming populations over time. This suggests that after the initial expansion of early farmers, there were no further long-range migrations substantial plenty to homogenize the farming population, and that farming and hunter-gatherer populations existed next for many centuries, with ongoing gradual admixture throughout the 5th to 4th millennia BCE (rather than a single admixture upshot on initial contact).[22] Admixture rates varied geographically; in the late Neolithic, WHG beginnings in farmers in Hungary was at around 10%, in Deutschland around 25% and in Iberia equally high as l%.[23]

Linguistic communication [edit]

Neolithic cultures in Europe in ca. 4000–3500 BCE.

In that location is no straight bear witness of the languages spoken in the Neolithic. Some proponents of paleolinguistics attempt to extend the methods of historical linguistics to the Stone Age, but this has little academic back up. Criticising scenarios which envision for the Neolithic simply a small number of language families spread over huge areas of Europe (as in modern times), Donald Ringe has argued on general principles of language geography (equally concerns "tribal", pre-land societies), and the scant remains of (plain indigenous) non-Indo-European languages attested in ancient inscriptions, that Neolithic Europe must take been a place of swell linguistic diversity, with many language families with no recoverable linguistic links to each other, much similar western Northward America prior to European colonisation.[24]

Discussion of hypothetical languages spoken in the European Neolithic is divided into two topics, Indo-European languages and "Pre-Indo-European" languages.

Early Indo-European languages are ordinarily assumed to accept reached Danubian (and maybe Primal) Europe in the Chalcolithic or early Bronze Historic period, e.g. with the Corded Ware or Beaker cultures (see also Kurgan hypothesis for related discussions). The Anatolian hypothesis postulates inflow of Indo-European languages with the early Neolithic. Old European hydronymy is taken by Hans Krahe to exist the oldest reflection of the early on presence of Indo-European in Europe.

Theories of "Pre-Indo-European" languages in Europe are built on scant evidence. The Basque language is the best candidate for a descendant of such a language, but since Basque is a language isolate, there is no comparative evidence to build upon. Theo Vennemann nevertheless postulates a "Vasconic" family, which he supposes had co-existed with an "Atlantic" or "Semitidic" (i. e., para-Semitic) group. Another candidate is a Tyrrhenian family unit which would have given rise to Etruscan and Raetic in the Iron Historic period, and peradventure also Aegean languages such as Minoan or Pelasgian in the Bronze Age.

In the north, a like scenario to Indo-European is thought to take occurred with Uralic languages expanding in from the due east. In item, while the Sami languages of the indigenous Sami people vest in the Uralic family, they show considerable substrate influence, thought to stand for one or more extinct original languages. The Sami are estimated to have adopted a Uralic linguistic communication less than 2,500 years ago.[25] Some traces of indigenous languages of the Baltic area take been suspected in the Finnic languages as well, but these are much more minor. In that location are early on loanwords from unidentified non-IE languages in other Uralic languages of Europe too.[26]

Listing of cultures and sites [edit]

Excavated dwellings at Skara Brae (Orkney, Scotland), Europe's near complete Neolithic village.

- Mesolithic

- Lepenski Vir civilization (tenth to seventh millennia)

- Megalithic culture (8th to second millennia)

- Early Neolithic

- Franchthi Cavern (20th to tertiary millennium) Greece. First European Neolithic site.

- Sesklo (seventh millennium) Greece.

- Starčevo-Criș culture (Starčevo I, Körös, Criş, Central Balkans, seventh to 5th millennia)

- Dudești culture (6th millennium)

- Center Neolithic

- La Almagra pottery culture (Andalusia, 6th to fifth millennium)

- Vinča civilization (6th to 3rd millennia)

- Hamangia civilization (Romania, Bulgaria c. 5200 to 4500 BC)

- Linear Ceramic civilization (6th to 5th millennia)

- Butmir culture (5100–4500 BC)

- Circular ditches

- Cardium pottery civilization (Mediterranean coast, seventh to 4th millennia)

- Pit–Comb Ware culture, a.k.a. Comb Ceramic culture (Northeast Europe, sixth to tertiary millennia)

- Cucuteni-Trypillian culture (Moldova, Ukraine, Romania, c. 5200 to 3500 BC)

- Ertebølle civilisation (Denmark, fifth to third millennia)

- Cortaillod culture (Switzerland, 4th millennium)

- Hembury culture (Britain, 5th to 4th millennia)

- Boian culture (Romania, Bulgaria c. 4300 to 3500 BC)

- Windmill Hill culture (Britain, 3rd millennium)

- Pfyn culture (Switzerland, 4th millennium)

- Globular Amphora civilization (Central Europe, 4th to 3rd millennia)

- Horgen civilization (Switzerland, 4th to 3rd millennia)

- Eneolithic (Chalcolithic)

A model of the prehistoric town of Los Millares, with its walls (Andalusia, Spain)

- Lengyel culture (5th millennium)

- A culture in Central Europe produced monumental arrangements of circular ditches between 4800 BCE and 4600 BCE.

- Varna culture (5th millennium)

- Funnelbeaker civilisation (4th millennium)

- Eutresis culture (Greece, 4th to tertiary Millennium BC)

- Yamnaya culture (3300 BCE to 2600 BCE)

- Baden civilisation (Central Europe, 4th to third millennia)

- Vučedol culture (Northward-west Balkans, Pannonian Plain, late 4th to 3rd millennia)

- Los Millares culture (Almería, Espana, quaternary to 2nd millennia)

- Corded Ware civilisation, a.thousand.a. Battle-axe or Single Grave culture (Northern Europe, 3rd millennium)

- Gaudo culture (3rd millennium, early Bronze Age, in Italian)

- Beaker culture (3rd to 2nd millennia, early Statuary Age)

- Stonehenge, Skara Brae

Megalithic [edit]

Some Neolithic cultures listed above are known for constructing megaliths. These occur primarily on the Atlantic coast of Europe, but in that location are as well megaliths on western Mediterranean islands.

- c. 5000 BCE: Constructions in Portugal (Évora). Emergence of the Atlantic Neolithic flow, the historic period of agriculture along the fertile shores of Europe.

- c. 4800 BCE: Constructions in Brittany (Barnenez) and Poitou (Bougon).

- c. 4000 BCE: Constructions in Brittany (Carnac), Portugal (Lisbon), Spain (Galicia and Andalusia), France (key and southern), Corsica, England, Wales, Northern Ireland (Banbridge) and elsewhere.

- c. 3700 BCE: Constructions in Ireland (Carrowmore and elsewhere) and Spain (Dolmen of Menga, Antequera Dolmens Site, Málaga).

- c. 3600 BCE: Constructions in England (Maumbury Rings and Godmanchester), and Malta (Ġgantija and Mnajdra temples).

- c. 3500 BCE: Constructions in Spain (Dolmen of Viera, Antequera Dolmens Site, Málaga, and Guadiana), Ireland (south-due west), France (Arles and the due north), northward-westward and key Italy (Piedmont, Valle d'Aosta, Liguria and Tuscany), Mediterranean islands (Sardinia, Sicily, Malta) and elsewhere in the Mediterranean, Kingdom of belgium (north-east) and Federal republic of germany (cardinal and south-west).

- c. 3400 BCE: Constructions in Republic of ireland (Newgrange), Netherlands (north-east), Germany (northern and central) Sweden and Kingdom of denmark.

- c. 3200 BCE: Constructions in Malta (Ħaġar Qim and Tarxien).

- c. 3000 BCE: Constructions in French republic (Saumur, Dordogne, Languedoc, Biscay, and the Mediterranean coast), Spain (Los Millares), Belgium (Ardennes), and Orkney, as well equally the first henges (circular earthworks) in Britain.

- c. 2900 BCE: Constructions in Espana (Tholos of El Romeral, Antequera Dolmens Site, Málaga)

- c. 2800 BCE: Climax of the megalithic Funnel-chalice civilisation in Kingdom of denmark, and the construction of the henge at Stonehenge.

Run into also [edit]

- Chalcolithic Europe

- Germanic substrate hypothesis

- Indo-Iranian migration

- Neolithic tomb

- Old European culture

- Pre-Indo-European languages

- Proto-Indo-European language

- Proto-Indo-Europeans

- Vinča symbols

References [edit]

- ^ Ammerman & Cavalli-Sforza 1971.

- ^ a b c Original text published under Creative Eatables license CC BY 4.0: Shukurov, Anvar; Sarson, Graeme R.; Gangal, Kavita (2014). "The Near-Eastern Roots of the Neolithic in South Asia". PLOS Ane. 9 (5): e95714. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...995714G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0095714. PMC4012948. PMID 24806472.

Cloth was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Cloth was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License - ^ Renfrew 1987.

- ^ Bellwood 2004.

- ^ Anthony 2007.

- ^ "Discovery of viii,000-yr-quondam veiled Female parent Goddess near Bulgaria'southward Vidin 'pushes back' Neolithic revolution in Europe". Archaeology in Bulgaria. 27 October 2018.

- ^ Bellwood 2004, pp. 68–nine.

- ^ Bellwood 2004, pp. 74, 118.

- ^ Subbaraman 2012.

- ^ a b Paul Rincon, Stonehenge: DNA reveals origin of builders. BBC News website, 16 Apr 2019

- ^ a b c Brace, Selina; Diekmann, Yoan; Booth, Thomas J.; van Dorp, Lucy; Faltyskova, Zuzana; Rohland, Nadin; Mallick, Swapan; Olalde, Iñigo; Ferry, Matthew; Michel, Megan; Oppenheimer, Jonas; Broomandkhoshbacht, Nasreen; Stewardson, Kristin; Martiniano, Rui; Walsh, Susan; Kayser, Manfred; Charlton, Sophy; Hellenthal, Garrett; Armit, Ian; Schulting, Rick; Craig, Oliver E.; Sheridan, Alison; Parker Pearson, Mike; Stringer, Chris; Reich, David; Thomas, Marker G.; Barnes, Ian (2019). "Ancient genomes bespeak population replacement in Early Neolithic U.k.". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 3 (5): 765–771. doi:ten.1038/s41559-019-0871-9. ISSN 2397-334X. PMC6520225. PMID 30988490.

- ^ Bellwood 2004, pp. 68–72.

- ^ Roger Highfield (2008-06-02). "Neolithic men were prepared to fight for their women". The Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235.

- ^ "German mass grave records prehistoric warfare". BBC News. 17 August 2015.

- ^ a b c Shennan & Edinborough 2007.

- ^ Timpson, Adrian; Colledge, Sue (September 2014). "Reconstructing regional population fluctuations in the European Neolithic using radiocarbon dates: a new case-study using an improved method". Journal of Archaeological Science. 52: 549–557. doi:x.1016/j.jas.2014.08.011.

- ^ Rascovan, Nicolás; Sjögren, Karl-Göran; Kristiansen, Kristian; Nielsen, Rasmus; Willerslev, Eske; Desnues, Christelle; Rasmussen, Simon (2019-01-10). "Emergence and Spread of Basal Lineages of Yersinia pestis during the Neolithic Decline". Jail cell. 176 (ane): 295–305.e10. doi:10.1016/j.prison cell.2018.11.005. ISSN 0092-8674. PMID 30528431.

- ^ Haak, Wolfgang; Lazaridis, Iosif; Patterson, Nick; Rohland, Nadin; Mallick, Swapan; Llamas, Bastien; Brandt, Guido; Nordenfelt, Susanne; Harney, Eadaoin; Stewardson, Kristin; Fu, Qiaomei (2015-06-11). "Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe". Nature. 522 (7555): 207–211. arXiv:1502.02783. Bibcode:2015Natur.522..207H. doi:ten.1038/nature14317. ISSN 0028-0836. PMC5048219. PMID 25731166.

- ^ Consortium, the Genographic; Cooper, Alan (9 November 2010). "Ancient DNA from European Early Neolithic Farmers Reveals Their Nigh Eastern Affinities". PLOS Biology. 8 (11): e1000536. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000536. ISSN 1545-7885. PMC2976717. PMID 21085689.

- ^ Lazaridis et al., "Ancient human genomes suggest iii ancestral populations for present-twenty-four hours Europeans", Nature, 513(7518), 18 September 2014, 409–413, doi: ten.1038/nature13673.

- ^ Lazaridis et al. (2014), Supplementary Information, p. 113.

- ^ Lipson et al., "Parallel palaeogenomic transects reveal complex genetic history of early on European farmers", Nature 551, 368–372 (16 Nov 2017) doi:10.1038/nature24476.

- ^ Lipson et al. (2017), Fig 2.

- ^ Ringe 2009.

- ^ Aikio 2004.

- ^ Häkkinen 2012.

Sources [edit]

- Aikio, Ante (2004). "An essay on substrate studies and the origin of Saami". In Hyvärinen, Irma; Kallio, Petri; Korhonen, Jarmo (eds.). Etymologie, Entlehnungen und Entwicklungen [Etymology, loanwords and developments]. Mémoires de la Société Néophilologique de Helsinki (in High german). Vol. 63. Helsinki: Société Néophilologique. pp. 5–34. ISBN978-951-9040-xix-half dozen.

- Ammerman, A. J.; Cavalli-Sforza, L. L. (1971). "Measuring the Rate of Spread of Early on Farming in Europe". Homo. 6 (4): 674–88. doi:ten.2307/2799190. JSTOR 2799190.

- Anthony, David W. (2007). The Horse, the Wheel, and Linguistic communication: How Statuary-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modernistic Globe. Princeton University Press. ISBN978-0-691-05887-0.

- Balaresque, Patricia; Bowden, Georgina R.; Adams, Susan M.; Leung, Ho-Yee; Male monarch, Turi Due east.; Rosser, Zoë H.; Goodwin, Jane; Moisan, Jean-Paul; Richard, Christelle; Millward, Ann; Demaine, Andrew G.; Barbujani, Guido; Previderè, Carlo; Wilson, Ian J.; Tyler-Smith, Chris; Jobling, Mark A. (2010). Penny, David (ed.). "A Predominantly Neolithic Origin for European Paternal Lineages". PLOS Biological science. viii (1): e1000285. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000285. PMC2799514. PMID 20087410.

- Ian Sample (nineteen Jan 2010). "Most British men are descended from aboriginal farmers". The Guardian.

- Barbujani, Guido; Bertorelle, Giorgio; Chikhi, Lounès (1998). "Evidence for Paleolithic and Neolithic Gene Flow in Europe". The American Journal of Human being Genetics. 62 (2): 488–92. doi:10.1086/301719. PMC1376895. PMID 9463326.

- Bar-Yosef, Ofer (1998). "The Natufian culture in the Levant, threshold to the origins of agriculture". Evolutionary Anthropology: Bug, News, and Reviews. half dozen (5): 159–77. doi:x.1002/(SICI)1520-6505(1998)6:five<159::AID-EVAN4>3.0.CO;2-seven.

- Battaglia, Vincenza; Fornarino, Simona; Al-Zahery, Nadia; Olivieri, Anna; Pala, Maria; Myres, Natalie M; King, Roy J; Rootsi, Siiri; Marjanovic, Damir; Primorac, Dragan; Hadziselimovic, Rifat; Vidovic, Stojko; Drobnic, Katia; Durmishi, Naser; Torroni, Antonio; Santachiara-Benerecetti, A Silvana; Underhill, Peter A; Semino, Ornella (2008). "Y-chromosomal testify of the cultural improvidence of agronomics in southeast Europe". European Journal of Human Genetics. 17 (half dozen): 820–30. doi:ten.1038/ejhg.2008.249. PMC2947100. PMID 19107149.

- Bellwood, Peter (2004). Commencement Farmers: The Origins of Agricultural Societies. Blackwell Publishers. ISBN978-0-631-20566-1.

- Brace, C. Loring; Seguchi, Noriko; Quintyn, Conrad B.; Play tricks, Sherry C.; Nelson, A. Russell; Manolis, Sotiris One thousand.; Qifeng, Pan (2005). "The questionable contribution of the Neolithic and the Statuary Age to European craniofacial form". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 103 (1): 242–7. Bibcode:2006PNAS..103..242B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0509801102. JSTOR 30048282. PMC1325007. PMID 16371462.

- Busby, George B. J.; Brisighelli, Francesca; Sánchez-Diz, Paula; Ramos-Luis, Eva; Martinez-Cadenas, Conrado; Thomas, Marking 1000.; Bradley, Daniel G.; Gusmão, Leonor; Winney, Bruce; Bodmer, Walter; Vennemann, Marielle; Coia, Valentina; Scarnicci, Francesca; Tofanelli, Sergio; Vona, Giuseppe; Ploski, Rafal; Vecchiotti, Carla; Zemunik, Tatijana; Rudan, Igor; Karachanak, Sena; Toncheva, Draga; Anagnostou, Paolo; Ferri, Gianmarco; Rapone, Cesare; Hervig, Tor; Moen, Torolf; Wilson, James F.; Capelli, Cristian (2011). "The peopling of Europe and the cautionary tale of Y chromosome lineage R-M269". Proceedings of the Purple Order B: Biological Sciences. 279 (1730): 884–92. doi:ten.1098/rspb.2011.1044. PMC3259916. PMID 21865258.

- Cavalli-Sforza, LL (1997). "Genes, peoples, and languages". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United states of america. 94 (fifteen): 7719–24. Bibcode:1997PNAS...94.7719C. doi:x.1073/pnas.94.15.7719. PMC33682. PMID 9223254.

- Chikhi, L.; Destro-Bisol, G.; Bertorelle, G.; Pascali, 5.; Barbujani, K. (1998). "Clines of nuclear Dna markers propose a largely Neolithic beginnings of the European cistron pool". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 95 (fifteen): 9053–viii. Bibcode:1998PNAS...95.9053C. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.xv.9053. JSTOR 45884. PMC21201. PMID 9671803.

- Cruciani, F.; et al. (2007). "Tracing by human male person movements in northern/eastern Africa and western Eurasia: new clues from Y-chromosomal haplogroups E-M78 and J-M12". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 24 (6): 1300–1311. doi:10.1093/molbev/msm049. PMID 17351267.

- Derenko, Miroslava; Malyarchuk, Boris; Denisova, Galina; Perkova, Maria; Rogalla, Urszula; Grzybowski, Tomasz; Khusnutdinova, Elza; Dambueva, Irina; Zakharov, Ilia (2012). Kivisild, Toomas (ed.). "Complete Mitochondrial Dna Analysis of Eastern Eurasian Haplogroups Rarely Found in Populations of Northern Asia and Eastern Europe". PLOS ONE. vii (2): e32179. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...732179D. doi:x.1371/journal.pone.0032179. PMC3283723. PMID 22363811.

- Di Giacomo, F.; Luca, F.; Popa, L. O.; Akar, Northward.; Anagnou, N.; Banyko, J.; Brdicka, R.; Barbujani, 1000.; Papola, F.; Ciavarella, Grand.; Cucci, F.; Di Stasi, L.; Gavrila, L.; Kerimova, Thousand. G.; Kovatchev, D.; Kozlov, A. I.; Loutradis, A.; Mandarino, V.; Mammi', C.; Michalodimitrakis, Eastward. Northward.; Paoli, G.; Pappa, K. I.; Pedicini, G.; Terrenato, L.; Tofanelli, S.; Malaspina, P.; Novelletto, A. (2004). "Y chromosomal haplogroup J as a signature of the postal service-neolithic colonization of Europe". Homo Genetics. 115 (v): 357–71. doi:10.1007/s00439-004-1168-9. PMID 15322918. S2CID 18482536.

- Dokládal, Milan; Brožek, Josef (1961). "Physical Anthropology in Czechoslovakia: Recent Developments". Current Anthropology. two (5): 455–77. doi:10.1086/200228. JSTOR 2739787. S2CID 161324951.

- Dupanloup, I.; Bertorelle, G; Chikhi, 50; Barbujani, Chiliad (2004). "Estimating the Affect of Prehistoric Admixture on the Genome of Europeans". Molecular Biological science and Development. 21 (seven): 1361–72. doi:10.1093/molbev/msh135. PMID 15044595. S2CID 17665038.

- Häkkinen, Jaakko (2012). "Early on contacts between Uralic and Yukaghir" (PDF). Suomalais-Ugrilaisen Seuran Toimituksia − Mémoires de la Société Finno-Ougrienne (264): 91–101. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- Lacan, Marie; Keyser, Christine; Ricaut, François-Xavier; Brucato, Nicolas; Tarrus, Josep; Bosch, Affections; Guilaine, Jean; Crubezy, Eric; Ludes, Bertrand (2011). "Ancient Deoxyribonucleic acid suggests the leading role played past men in the Neolithic dissemination". Proceedings of the National University of Sciences. 108 (45): 18255–ix. Bibcode:2011PNAS..10818255L. doi:10.1073/pnas.1113061108. PMC3215063. PMID 22042855.

- Renfrew, Colin (1987). Archeology and Language. London: Jonathan Greatcoat. ISBN978-0-521-38675-3.

- Ricaut, F. 10.; Waelkens, M. (2008). "Cranial Discrete Traits in a Byzantine Population and Eastern Mediterranean Population Movements". Man Biology. 80 (5): 535–64. doi:10.3378/1534-6617-80.v.535. PMID 19341322. S2CID 25142338.

- Richards, 1000; Côrte-Real, H; Forster, P; MacAulay, V; Wilkinson-Herbots, H; Demaine, A; Papiha, South; Hedges, R; Bandelt, HJ; Sykes, B (1996). "Paleolithic and neolithic lineages in the European mitochondrial gene pool". American Periodical of Human Genetics. 59 (1): 185–203. PMC1915109. PMID 8659525.

- Ringe, Don (Jan half-dozen, 2009). "The Linguistic Diversity of Ancient Europe". Linguistic communication Log. Mark Liberman. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- Rosser, Zoë H.; Zerjal, Tatiana; Hurles, Matthew E.; Adojaan, Maarja; Alavantic, Dragan; Amorim, António; Amos, William; Armenteros, Manuel; Arroyo, Eduardo; Barbujani, Guido; Beckman, Thou; Beckman, 50; Bertranpetit, J; Bosch, E; Bradley, DG; Brede, G; Cooper, G; Côrte-Existent, HB; De Knijff, P; Decorte, R; Dubrova, YE; Evgrafov, O; Gilissen, A; Glisic, S; Gölge, M; Hill, EW; Jeziorowska, A; Kalaydjieva, Fifty; Kayser, Grand; Kivisild, T (2000). "Y-Chromosomal Diversity in Europe is Clinal and Influenced Primarily by Geography, Rather than by Linguistic communication". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 67 (six): 1526–43. doi:10.1086/316890. PMC1287948. PMID 11078479.

- Semino, Ornella; Magri, Chiara; Benuzzi, Giorgia; Lin, Alice A.; Al-Zahery, Nadia; Battaglia, Vincenza; MacCioni, Liliana; Triantaphyllidis, Costas; Shen, Peidong; Oefner, Peter J.; Zhivotovsky, Lev A.; King, Roy; Torroni, Antonio; Cavalli-Sforza, L. Luca; Underhill, Peter A.; Santachiara-Benerecetti, A. Silvana (2004). "Origin, Diffusion, and Differentiation of Y-Chromosome Haplogroups Eastward and J: Inferences on the Neolithization of Europe and After Migratory Events in the Mediterranean Area". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 74 (5): 1023–34. doi:10.1086/386295. PMC1181965. PMID 15069642.

- Semino, O.; Passarino, G; Oefner, PJ; Lin, AA; Arbuzova, S; Beckman, LE; De Benedictis, Thou; Francalacci, P; Kouvatsi, A; Limborska, S; Marcikiae, G; Mika, A; Mika, B; Primorac, D; Santachiara-Benerecetti, As; Cavalli-Sforza, LL; Underhill, PA (2000). "The Genetic Legacy of Paleolithic Human being sapiens sapiens in Extant Europeans: A Y Chromosome Perspective". Science. 290 (5494): 1155–9. Bibcode:2000Sci...290.1155S. doi:10.1126/science.290.5494.1155. PMID 11073453.

- Shennan, Stephen; Edinborough, Kevan (2007). "Prehistoric population history: From the Late Glacial to the Late Neolithic in Central and Northern Europe". Journal of Archaeological Science. 34 (eight): 1339–45. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2006.x.031.

- Subbaraman, Nidhi (2012). "Art of cheese-making is seven,500 years former". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2012.12020. S2CID 180646880.

- Haak, Wolfgang; Forster, Peter; Bramanti, Barbara; Matsumura, Shuichi; Brandt, Guido; Tänzer, Marc; Villems, Richard; Renfrew, Colin; et al. (2005). "Aboriginal DNA from the First European Farmers in 7500-Twelvemonth-Old Neolithic Sites". Science. 310 (5750): 1016–8. Bibcode:2005Sci...310.1016H. doi:ten.1126/scientific discipline.1118725. ISSN 1095-9203. PMID 16284177. S2CID 11546893.

- Zvelebil, Marek (1989). "On the transition to farming in Europe, or what was spreading with the Neolithic: a respond to Ammerman (1989)". Antiquity. 63 (239): 379–83. doi:x.1017/S0003598X00076110. Archived from the original on 2013-10-30.

- Zvelebil, Marek (2009). "Mesolithic prelude and neolithic revolution". In Zvelebil, Marek (ed.). Hunters in Transition: Mesolithic Societies of Temperate Eurasia and Their Transition to Farming. Cambridge University Press. pp. 5–15. ISBN978-0-521-10957-four.

- Zvelebil, Marek (2009). "Mesolithic societies and the transition to farming: problems of time, scale and organisation". In Zvelebil, Marek (ed.). Hunters in Transition: Mesolithic Societies of Temperate Eurasia and Their Transition to Farming. Cambridge Academy Printing. pp. 167–88. ISBN978-0-521-10957-iv.

Farther reading [edit]

- Bellwood, Peter (2001). "Early Agriculturalist Population Diasporas? Farming, Languages, and Genes". Almanac Review of Anthropology. 30: 181–207. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.30.1.181. JSTOR 3069214. S2CID 12157394.

- Cavalli-Sforza, Luigi Luca; Menozzi, Paolo; Piazza, Alberto (1994). The History and Geography of Human Genes. Princeton University Press. ISBN978-0-691-08750-4.

- Cavalli-Sforza, Luigi Luca (2001). Genes, Peoples, and Languages. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN978-0-520-22873-3.

- Gimbutas, Marija (1989). The Language of the Goddess . Harper & Row. ISBN978-0-06-250356-5.

- Fu Q, Posth C, Hajdinjak Thou, Petr Grand, Mallick S, Fernandes D, et al. (June 2016). "The genetic history of Ice Age Europe". Nature. 534 (7606): 200–five. Bibcode:2016Natur.534..200F. doi:10.1038/nature17993. hdl:10211.3/198594. PMC4943878. PMID 27135931.

External links [edit]

- Hofmanová, Zuzana; Kreutzer, Susanne; Hellenthal, Garrett; et al. (2016). "Early on farmers from across Europe straight descended from Neolithic Aegeans". Proceedings of the National University of Sciences. 113 (25): 6886–6891. doi:x.1073/pnas.1523951113. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC4922144. PMID 27274049.

- The genetic structure of the world's get-go farmers, Lazaridis et al, 2016

- Massive migration from the steppe is a source for Indo-European languages in Europe, Haak et al, 2015

- Population genomics of Bronze Age Eurasia, Allentoft et al, 2015

- Viii thousand years of natural selection in Europe, Mathieson et al, 2015

- "The Equus caballus, the Cycle and Language, How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes shaped the Modern World", David W Anthony, 2007

- General tabular array of Neolithic sites in Europe

- Mario Alinei, et al., Paleolithic Continuity Theory of Indo-European Origins

- culture.gouv.fr: Life along the Danube 6500 years agone

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neolithic_Europe

0 Response to "Changes in Art From Neolithic Period to Ancient Near East"

Post a Comment